In last year’s market outlook, I described the current state of global monetary policy as a giant exercise in price control, specifically, control of the cost of capital. An environment in which perpetually falling rates and equity premiums favor longer duration growth stocks, but hardly resulted in what might be described as widespread prosperity.

The (short-lived) revenge of the bottom half

During the grand re-opening of 2021, for a brief moment, dare I say it, things seemed to be going well. Bolstered by massive government stimulus and a strong job market, something remarkable happened to the average American household: they got richer.

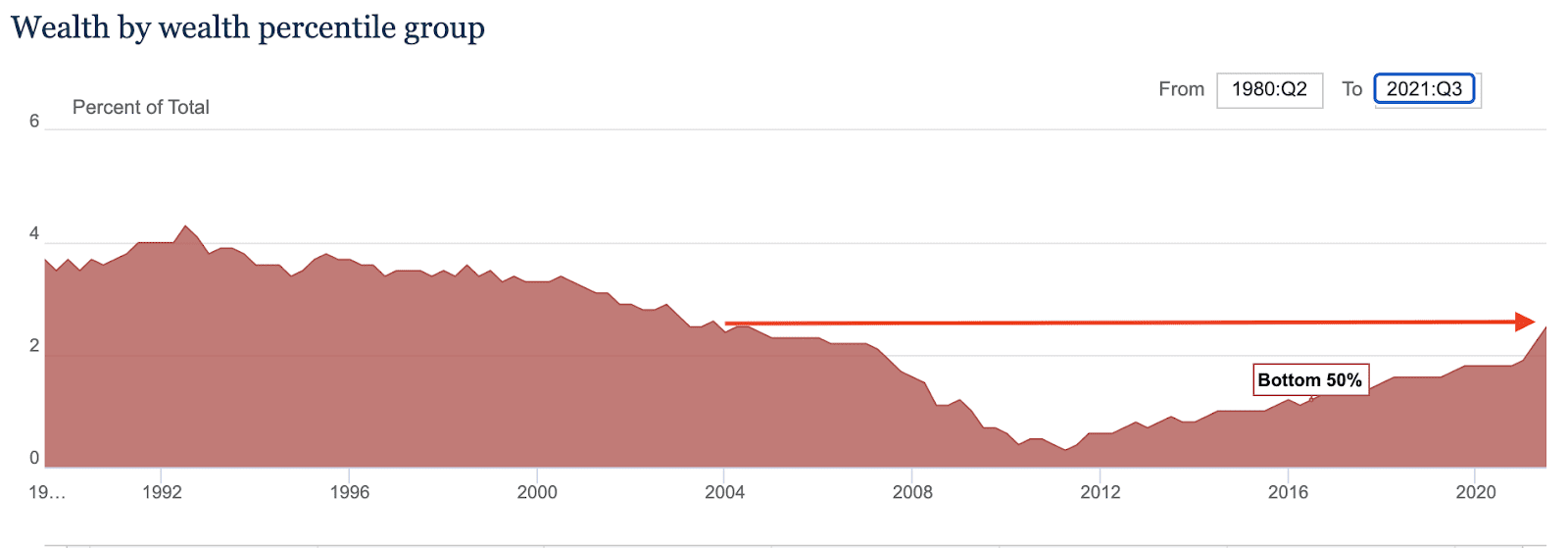

While household wealth rising is not surprising given equity, real estate, and cryptocurrency gains, what was truly remarkable was the relative gain attributable to the bottom 50% of American households, whose share of total wealth rose above 2.5% in Q3. While the percentage remains low in absolute terms, we had not seen this metric rise above 2% since the 2008 crisis, and 2.5% was last witnessed in the early 2000s.

A tight labor market, marked by the “great resignation” (an unusual number of people quitting their jobs), has certainly contributed to the slight, but noticeable, narrowing of inequalities. For the first time in years, the labor market appears to have shifted in favor of workers, who may be in a much stronger position to secure higher wages, strengthening their ability to accumulate wealth. Direct COVID relief payments and expended child credits also contributed to this continued improvement in household wealth.

Unfortunately, before anyone could celebrate a resurgence of the American middle class, a much bigger story would steal the headline: the return of inflation. In the short term, moderate levels of inflation can have a beneficial effect on the job market, support asset prices, ease debt burden, and even reduce income inequality. In the long term, however, the upside risk to inflation makes me less than enthusiastic about the potential for a continued trend in narrowing wealth inequalities.

While higher inflation means that everyone, in aggregate, gets poorer, some might get hurt more than others. Over time, cost pressures are likely to favor owners of productive assets at the expense of small savers and wage earners. A recent analysis by the Penn Wharton Budget Model already highlights the increasing burden on middle-income family budgets, who spent about 7% more in 2021 for the same products they bought in 2020 or in 2019. (3)

The era of low inflation never started, now it may be ending

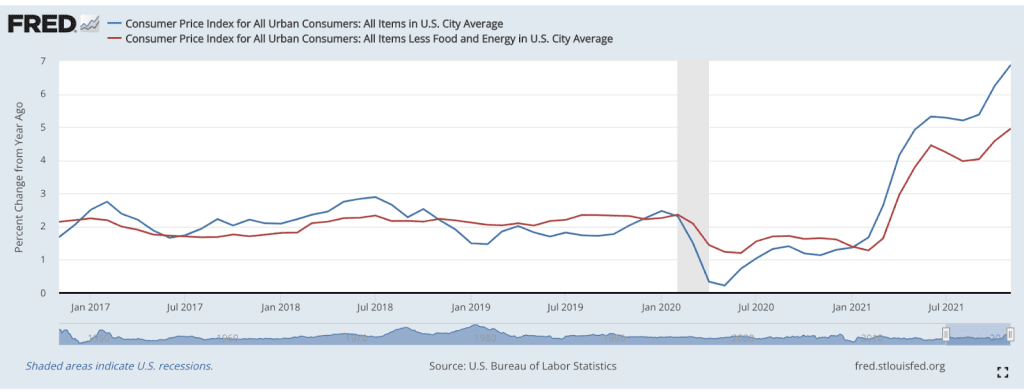

The return of higher inflation, in the form of her CPI numbers, was heralded as a momentous shift in the economic environment in 2021. After all, inflation has not been a major concern in most of the developed world in the last decade, some have even suggested that we lived in the era of low inflation, and central bank action certainly focused on fighting the perceived threat of deflation first and foremost.

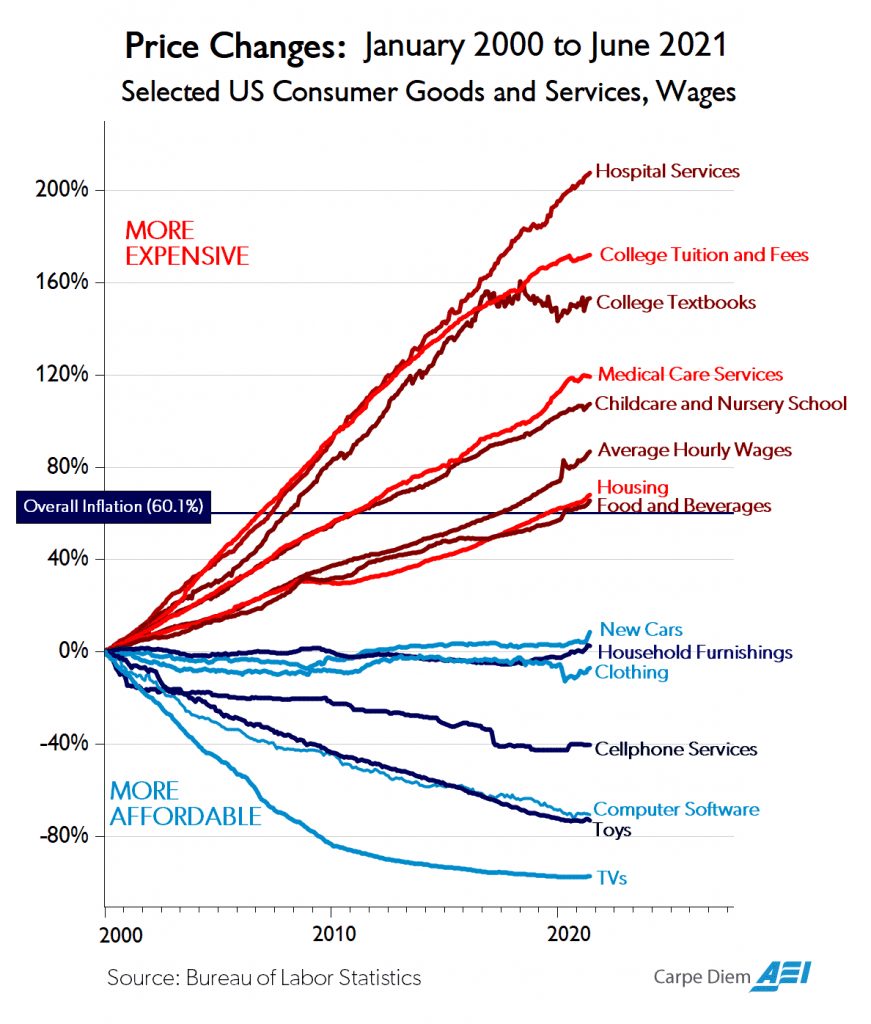

I was never a huge believer in the idea of a “low-inflation era.” To be sure, we may have had moderate levels of inflation on average, but more importantly, we’ve had an era of uneven, patchy inflation, where falling prices in some areas were offset but rapid increases in others.

What charts like the one above highlight, is that the supposed low-inflation era has, in fact, been an era of selective inflation. An era in which, broadly speaking, the price of things we don’t really need, like toys and electronics, has collapsed, but the price of things we need (say, food, housing, and healthcare…) has continued to rise.

In this environment, it is perhaps no surprise that middle-class households hardly seemed to reap the benefits of low prices. All else being equal, and despite the prevailing inflationist narrative: no inflation is good, deflation is even better (how often have you complained about prices at the store being too low?). For two decades deflation has been limited to a relatively small segment of largely discretionary expenses, while higher costs in other products may have actually reinforced inequalities.

Regardless of how the Consumer Price Index is composed, it is also important to recognize the limitation of the CPI (our policy makers’ main tool in measuring inflation). CPI is a complex set of data maintained by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Over the years, its methodology has been revised multiple times, and most recent adjustments have tended, in my opinion, to make monetary policy look better. Some of the most convenient CPI adjustments include: substitutions (the idea that if something is too expensive, we’ll just buy something else, say lemons instead of bananas…) or, even better: hedonics (an adjustment made when a price increase isn’t actually deemed to be a price increase, but just a reflection of improved product features). Not to mention the fact that shelter, one of the largest components of CPI, is for the most part not collected using a market-based mechanism. Instead, most of the CPI’s shelter data comes from something called Owner Equivalent Rent (OER). OER is basically a survey of homeowners, who get asked a simple question about how much they think their property could be rented for (imagine calling your parents who’ve lived in their house since 1976, and asking them what they think the rent is).

Regardless of how much I doubt inflation numbers, what became obvious in 2021 is that no amount of adjustments could make inflation look benign. Since March 2021, CPI inflation started exceeding the Federal Reserve’s 2% target and has continued to rise ever since.

In August 2020, the Federal Reserve implemented a new flexible approach to inflation, effectively warning the market that it may allow inflation to “run hot” for a while if it deemed necessary. We are now in our ninth month of excess inflation, and just how much more of these inflation numbers will be tolerated is unclear.

Over the last few years, central bank officials have often felt the subtle (or not so subtle) pressure to keep their policy stance accommodative (remember Donald Trump praising Janet Yellen for being a “low-interest person?). But politicians and the general public can be fickle, and the pressure to remain accommodative can just as easily morph into a pressure to tighten. If inflation continues to take hold, being a low-interest rate kind of person may not look so flattering anymore.

The trillion-dollar checking account

I have long been telling clients that the pandemic could, somewhat counterintuitively, be the catalyst for higher inflation. By pushing governments and central banks to implement a combination of both extremely loose monetary and fiscal policy, they may just have poured fuel on a fire that had been simmering for years underneath the low CPI numbers. While 2020 saw unprecedented levels of new debt issuance and stimulus, a lot of promises only reached full implementation in 2021, which may explain the sudden, but somewhat delayed, change in inflation dynamics.

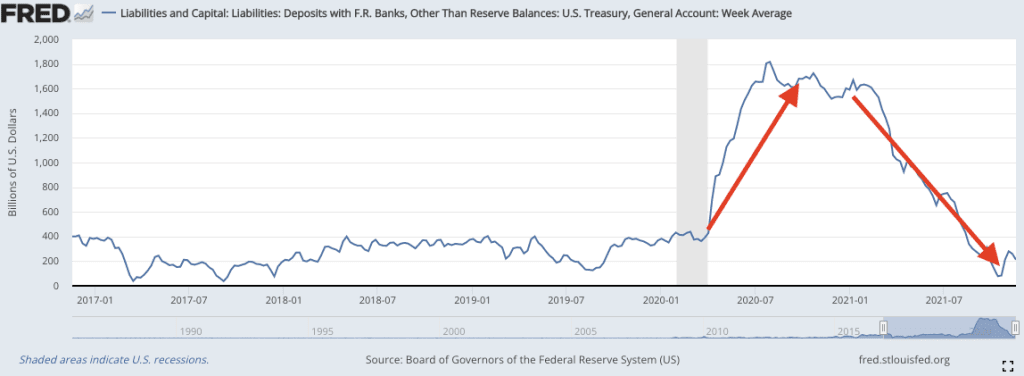

The U.S. Department of Treasury’s general account with the Federal Reserve (effectively, the government’s checking account) spent most of 2020 swelling up to unprecedented levels: normally fairly steady at a balance of around $300 billion, it reached a balance of $1.8 trillion in mid-2020 at the height of the pandemic.

In contrast, 2021 was truly the year of the great spending spree, when checks were finally cashed, even as treasury bill issuance slowed. $1.6 trillion was promptly spent in a matter of months between February and July 2021. As Citi’s market strategist Matt King highlighted back in February 2021: the flood of cash created by the drawdown in the treasury’s general account (TGA) risked tripling the amount of bank reserves, and pushing rates even further towards zero or negative territory: “surfeit of liquidity and a lack of places to put it – hence the rally in short-rates to almost zero, with the risk of their going negative.” As King further notes, “if relative ‘real’, inflation-adjusted Treasury yields fall, it could weaken the dollar sharply (…) at the global level the TGA effect will indeed prove highly significant.”

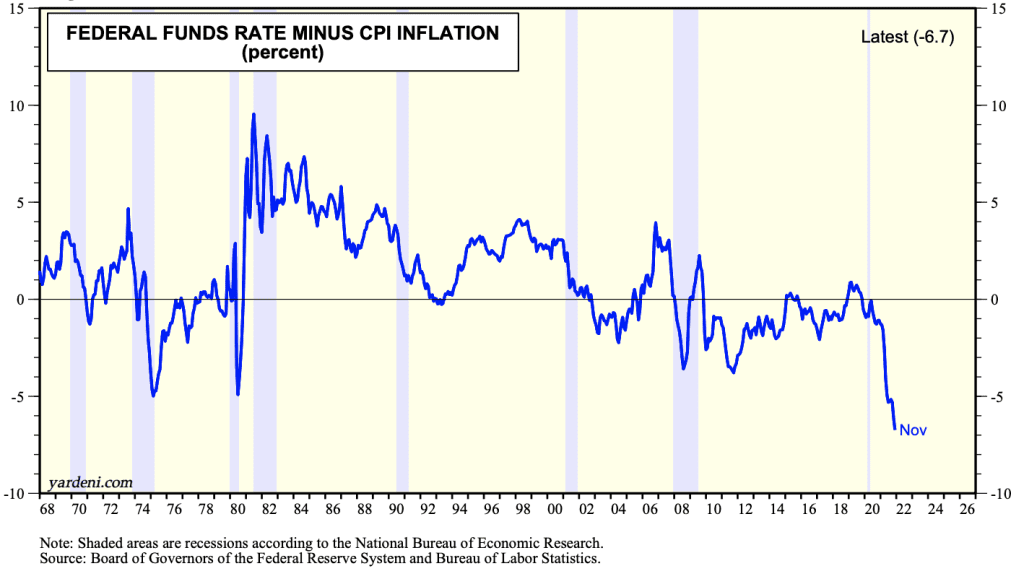

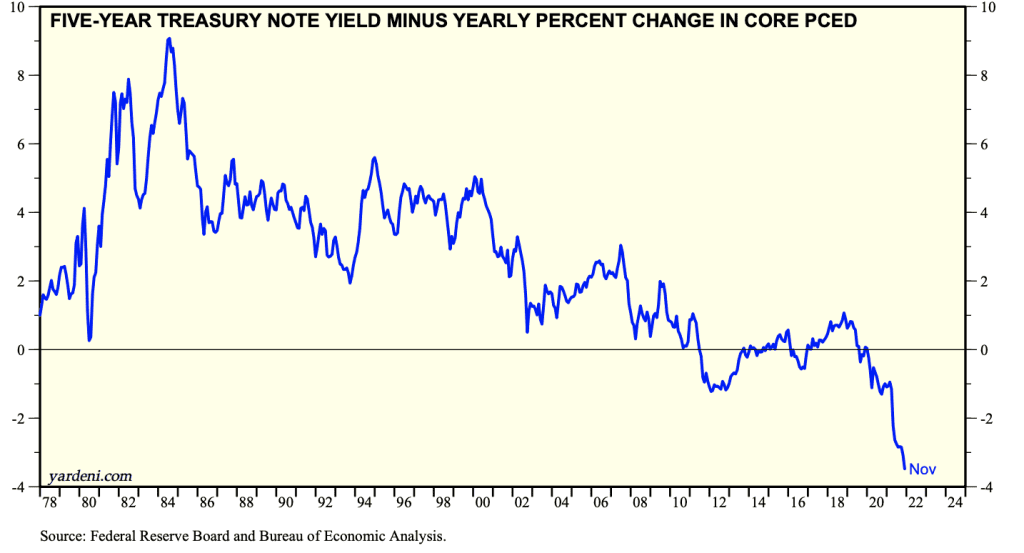

As shown above, real yield would indeed fall throughout 2021, to levels unprecedented in modern history, and one of the side effects of negative real yield may have been to propel the now-familiar “risk on” investment theme to new heights. We all thought money was cheap at -1% real rates in February, how about -6.5% In November?

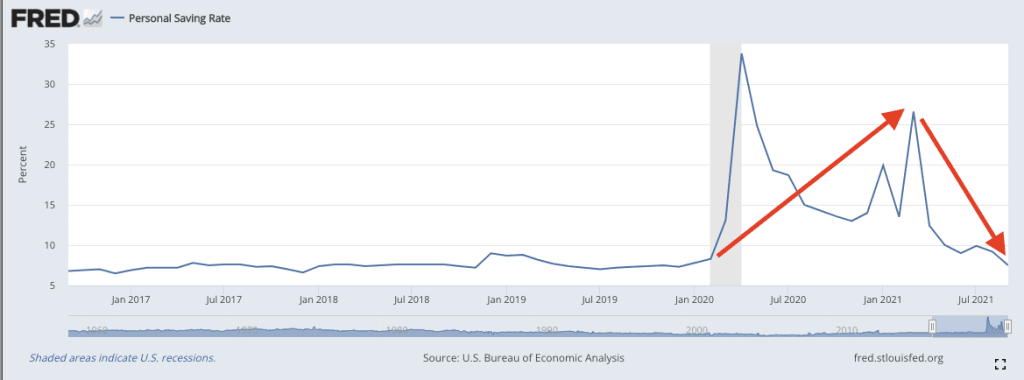

The treasury department wasn’t the only one spending. As it turns out, American households too were fast and loose with their checkbooks. Individual savings rates had risen during the pandemic and remained relatively elevated well into the beginning of 2021. Since March 2021 however, saving rates have fallen back to their pre-COVID levels.

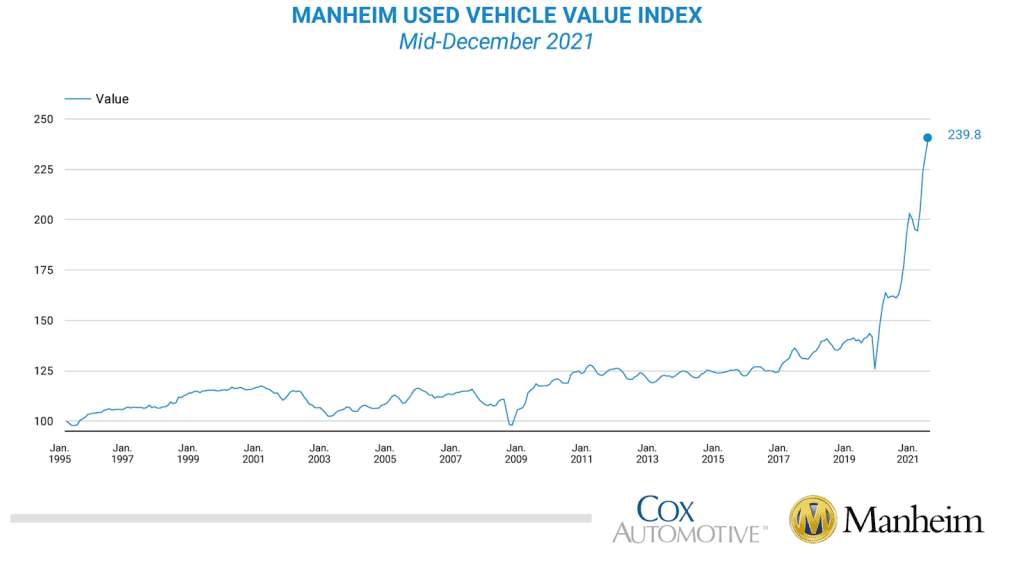

Against this backdrop, it is perhaps no surprise that the “buy everything” ethos, long limited only to financial assets, now seems to have spread into housing, commodities, energy, various consumption goods, and even used cars.

With gains of nearly 50% since December 2020, the Manheim Used Vehicle index outperformed both the S&P 500 and the Dow Jones in 2021.

Impossible choices

Over the last decade, central bankers have been almost entirely focused on supporting the economy. With the threat of inflation only a distant concern, there has been basically no downside to perpetually flooding markets with free money. To be sure, central bankers have been fairly successful in averting deflationary fears and consistently driving down real (inflation-adjusted) rates. With short-term rates at zero and longer-dated bonds at historic lows, many observers felt that yields had nowhere else to go. Real, inflation-adjusted rates have no such lower bound. And as much of what the recent spike in inflation will be heralded as a change of regime, in many ways, it can also be seen as the culmination of a broader trend in lower real rates that started many years ago – and arguably as far back as the mid-80s.

With real yield deeply negative, and central bank balance sheets at all-time highs, 2021 brought the scale of global monetary policy to yet another record-breaking year. However, for the first time in over a decade, inflation may truly force central banking officials to tighten policy this time. So far, policy response in the U.S. has been mainly limited to tougher talk and a planned reduction of the pace of asset purchases (the now-famous “tapering”). While FOMC guidance does indicate an expectation of multiple rate hikes in 2022, the Federal Reserve will be walking a very fine line as it looks to change course.

One of the paradoxes of the current environment is the continued flattening of the yield curve. A flood of bank liquidity may have contributed to the collapse in real short-term rates but has not resulted in any real upward shift in long-dated bond yields. This could be interpreted in numerous ways. Perhaps the bond market is simply not buying the idea of long-term inflation or may think it raises the probability of a policy mistake (excessive tightening leading to a deflationary crisis), or perhaps the Federal Reserve’s bond-buying program has simply distorted bond prices to such a degree that rates no longer reflect any realistic growth and inflation expectations. Whatever the case may be, hiking rates in this environment would mean running the risk of yield curve inversion: a situation where short-term rates would exceed long-term rates. While not always predictive of a crisis, an inverted yield curve generally sends a very negative signal and isn’t consistent with a healthy economy, in which opportunity cost should correlate positively with time.

Central banking officials are very aware of the risk, and the issue of curve flatness was explicitly brought up by members of the FOMC in their December meeting. There is a certain common-sense logic to the idea that, before resorting to traditional monetary tightening policies (raising short-term rates) the Federal Reserve should first get rid of the more exotic, experimental, crisis-time measures, such as quantitative easing. Doing so may allow long-term interest rates to rise, resulting in a more constructive environment in which to hike short-term rates. After all, if the economy is strong, to the point of raising rates, why have QE at all? That does not seem to be what committee members are thinking. In fact, according to their latest minutes, they seem intent on doing the exact opposite: begin to raise rates as early as March 2022, and then tackle balance sheet reduction. Even so, balance sheet reduction would not resemble a complete termination of their bond-buying program, but would probably involve a monthly cap on the amounts of “runoffs” (treasury bonds allowed to mature without being reinvested). Assuming that the monthly cap on runoffs does not exceed monthly maturities, the net effect of this policy may be that the Federal Reserve will be continuing to buy billions of dollars worth of bonds every month for the foreseeable future. Presumably with the hope that slowing the pace of balance sheet reduction will act as a buffer against the possible negative effects of rate hikes.

In this balancing act between tapering and rate hikes, one might perhaps perceive a subtle acknowledgment that central bank officials have made themselves into de-facto custodians of stock prices. After all, their previous attempts at an interest rate hike cycle in 2018 ended in a 20% market sell-off and had to be promptly reversed. At today’s valuations, a similar sell-off would wipe out nearly 10 trillion dollars of value from the S&P 500 alone. Ultimately, the message buried in the complex mix of central banking rhetoric may simply be that the Federal Reserve intends to stay behind the curve in its attempts to tackle inflation. That it intends to tighten policy slowly, while remaining accommodative and relying on the magic of negative real rates to support asset prices and the economy, tightening without tightening. Exactly how long they can get away with this in the face of higher inflation is anyone’s guess. Given the huge political stakes around issues of wealth inequalities, and with midterm elections around the corner, I expect pressure on the Federal Reserve to ramp up over the coming months. Backed into a corner, central banking officials may just have to pick between continuing to support market valuations and curbing cost pressures. However things turn out, 2022 may very well be the year when investors and US households alike realize that free money does have a cost after all.

2022 Investment & Market Outlook Guide

Syl Michelin’s piece is part of Walkner Condon’s 2022 Investment & Market Outlook Guide, a comprehensive reflection of 2021 and glimpse at the factors impacting the year ahead in 2022.